The debate over Modern Monetary Theory

Thanks to a subscriber for this report from UBS which may be of interest. Here is a section:

Here is a link to the full report and here is a section from it:

The debate about MMT is going to continue. National deficits will grow since policymakers as diverse as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Larry Kudlow both agree they are not anathema to prosperity. Ultimately, the most important thing to know about ideas like MMT, Brexit, or corporate tax cuts is not if we think they come from the dark side of the force or not, but what the impact is likely to be on our portfolios as these various policies are enacted, retracted, and tried again.

Thinking about the impact of MMT can help us create a mindset that builds more robust portfolios. We should approach the subject with an open mind and a lack of preconceptions – a concept Zen Buddhists call Shoshin, a “beginner’s mind.” For example, we need to imagine a world where the traditional economic cycle could be dead. Typically, once the Federal Reserve had started to raise rates, we would expect the cycle to mature, as it would hike rates enough to choke off inflation and growth. However, whether we call it MMT or not, it is possible that we may be in a world of more expansive fiscal policy and continued easy monetary policy now that the Fed is on hold. That combination could extend the cycle further and sustain the rally in risk assets. For us, inflation remains the most important variable to watch.

Recent history has shown how deficit spending can have a real impact on your portfolio. Abenomics was introduced at the start of 2013, and by mid-2015 the Nikkei had doubled, bond yields had fallen to as low as 20bps, and USDJPY had moved from 86 to 125. More recently, President Trump’s 2017 corporate tax cuts provided a substantial boost to companies’ earnings, helping propel the S&P 500 to an all-time high in September 2018. And last year’s short-lived spike in Italian two-year bond yields on concerns of a sovereign debt downgrade provided an opportunity to profit from fears about deficits.

Yet over the longer term, we need to design portfolios that are robust enough to survive even if things are not different this time. Ultimately, high deficits may yet lead to higher inflation, higher interest rates, and currency devaluation. We must assume that the very different monetary and fiscal policies pursued by major nations will not end equally well. There will be winners and there will be losers. So while it is important to maintain sufficient assets in the home currency of your liabilities, now more than ever is a time to diversify into some of the other regions of the globe pursuing different policies.

The discussion about Modern Monetary Theory is inconvenient because it brings into the public eye what governments and central banks have been doing all along. It is very convenient to sport a façade of adherence to the ideal of balanced budgets, spending within your means, low inflation and preservation of purchasing power. However, if we look at the history of government these ideals are rarely realised. Meanwhile, deficit spending, lavish social programs and rising debt ratios are the rule rather than the exception.

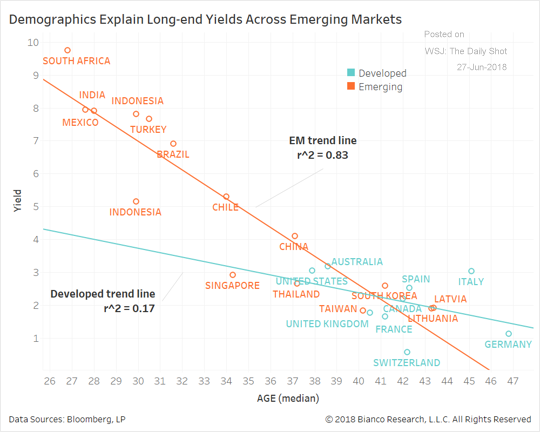

This graphic demonstrates a correlation between median age in an economy and the government bond yield. Correlation does not infer causation but it certainly gives us something to think about. Aging populations have made their biggest purchases and tend to spend more on healthcare than consumption as life follows its natural course. The countries with the world’s oldest populations have the lowest yields, namely Japan and Germany. Italy is an exception to that rule which is another reason it is unlikely to ever leave the Eurozone.

Central banks are charged with supporting growth. If a government decides to just start issuing debt to meet its liabilities, yields would naturally rise and the economy would fall into recession. At that point the central bank has no choice but to lower rates and/or start buying the bonds. Therefore, to think a central bank would go on strike is a nonsense. The only way the cycle breaks is if inflation picks up and not in a small way. That would eventually usher in a Volcker-type character to tip the cycle in the other direction. We are a long way from that eventuality and demographics play an important role in that determination.

The logical conclusion is asset price inflation remains a significant factor and we are likely to see a bubble develop before the eventual denouement.

Back to top