A Grim Outlook for the Economy, Stocks

Thanks to a subscriber for this interview of Stephanie Pomboy expressing a bearish view which appeared in Barron’s. Here is a section:

The presumption supporting equity prices is that all the bad news we’ve seen this year has been due to anomalies—the lagged effect of the strong dollar and weaker energy prices as well as Brexit. Everyone is looking for a significant second-half rebound for earnings and GDP—when the clouds will part and the sun will come out. I strongly believe that won’t happen, in large part because of inventories. Inventory accumulation has been explosive.

What’s caused this growth in inventories?

It isn’t because companies ramped up production. Companies aren’t using cheap capital to increase production and capital expenditures, but are lavishing money on shareholders instead. They bought the lie that consumer spending would turn up any moment, and produced at the same pace. Now they find themselves with a monster inventory overhang. Inventory-to-sales ratios across a variety of industries—manufacturing, machinery, autos, wholesale—are at the highest level since 2009. In prior inventory liquidation cycles, nominal GDP growth is cut in half during the liquidation phase. As for profits, we’re starting with five negative quarters and we haven’t even begun the inventory liquidation cycle. So the second half will be a real eye-opener.In your view, today’s too-low rates will cause the next financial crisis. Describe it.

In the past rates that were too high were the trigger. Not this time. No. 1, we have basically bankrupted corporate and state and local pensions by having rates at these repressive levels. If you lay on top of that a decline in equity prices, there will be a scramble to plug holes in pensions. Obviously if a state or local government has to divert funds to plugging its pension, it won’t build more roads. The corporate sector has the luxury of kicking the can down the road, and because their spending has been on buybacks, not plants and equipment, the economy would suffer less. For S&P 1500 companies, the pension deficit is roughly $560 billion, but for state and local governments, it’s $1.2 trillion. According to the Center for Retirement Research, if you used a more conservative discount rate, the unfunded liability would go to $4 trillion.No. 2, you’re pushing consumers to the brink as they try to save enough for retirement at zero rates. You’re already seeing a reluctant return to credit-card usage, a clear sign of distress—they are charging what they previously paid with cash. The credit-card delinquency rate is picking up.

The way people generally think about pensions is that you accumulate a pot of money over your lifetime, purchase an annuity with a yield greater than your living costs and a maturity that extends to the end of one’s life. Of course that is not realisable in practice so pension funds have to manage the duration of the overall portfolio so they can plan to meet future liabilities with some degree of accuracy.

The problem is that in formulating their models they typically assume a 7% yield. That’s OK when nominal interest rates are somewhere close to that level but with rates close to zero, for nearly a decade, they have no choice but to rely on capital appreciation to make up for the absence of yield. The alternative is to take on a lot more risk to capture the yield they require. For example, and this is obviously not a recommendation, Rwanda’s senior unsecured US Dollar B+ 2023 bond currently yields 6.195%.

As with any momentum move the real problems don’t kick in until the trend changes. Right now yields might be at historic lows but capital appreciation is more than making up for the loss of income when one calculates total return. If on the other hand interest rates rise and bonds prices fall then pension funds would have no choice than to mark to market and the gap between assets and future liabilities becomes a real problem. More than any other factor that is perhaps the most compelling argument for the Fed being reluctant to raise rates.

The fact corporate profits have been declining represents a problem for equities but liquidity is potentially more important. If the Fed is slow in raising rates, or if it joins other central banks in re-enacting quantitative easing, then we can expect asset price inflation which would be positive for equity prices in nominal terms.

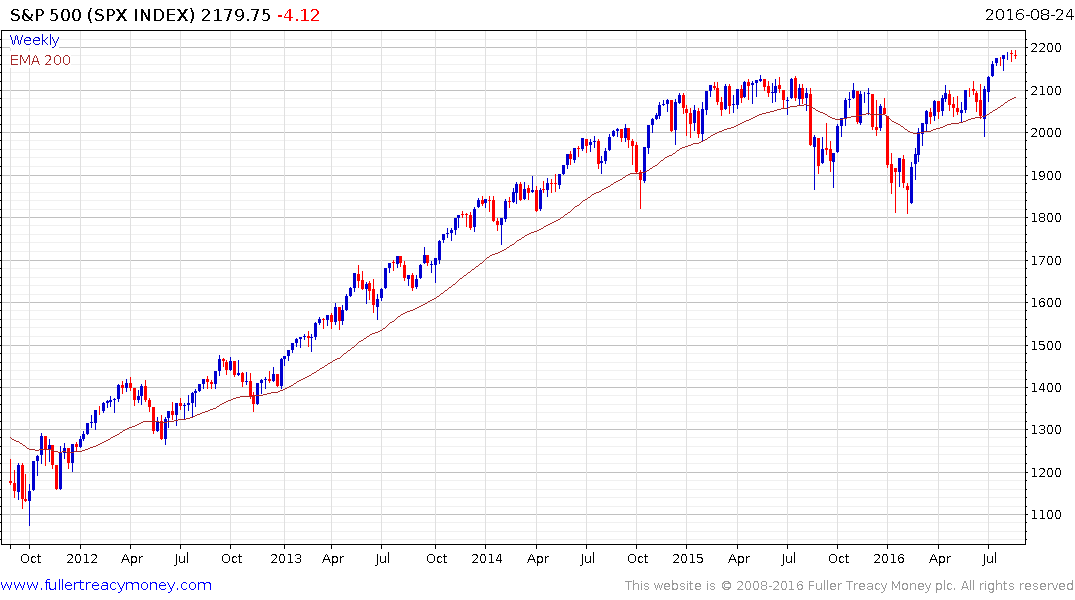

The S&P500 has been mostly inert since breaking out in July and a deeper consolidation of gains is possible. However a sustained move below the trend mean would be required to question the overall upward bias.

Back to top